This paper was developed within the scope of a PhD thesis that intends to characterize the use of mobile applications by the students of the University of Aveiro during class time. The main purpose of this paper is to present the results of an initial pilot study that aimed to fine-tune data collection methods in order to gather data that reflected the practices of the use of mobile applications by students in a higher education institution during classes. In this paper we present the context of the pilot, its technological settings, the analysed cases and the discussion and conclusions carried out to gather mobile applications usage data logs from students of an undergraduate degree on Communication Technologies.

Our study gathered data from 77 participants, taking theoretical classes in the Department of Communication and Arts at the University of Aveiro. The research was based on the Grounded Theory method approach aiming to analyse the logs from the access points of the University. With the collected data, a profile of the use of mobile devices during classes was drawn.

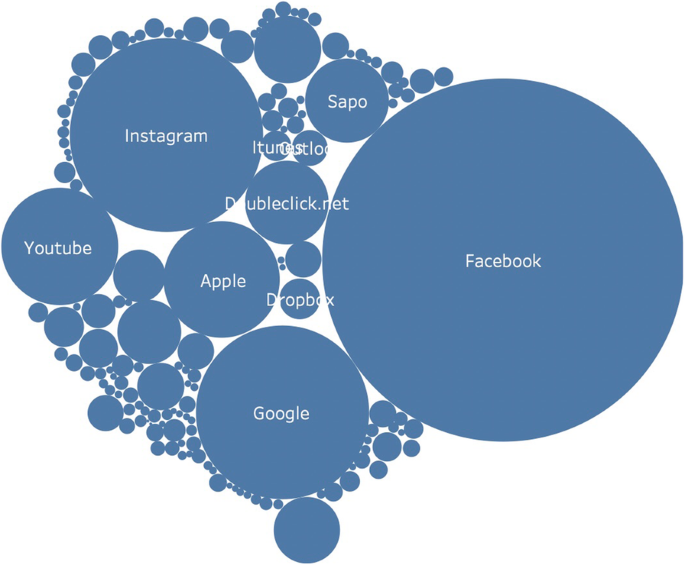

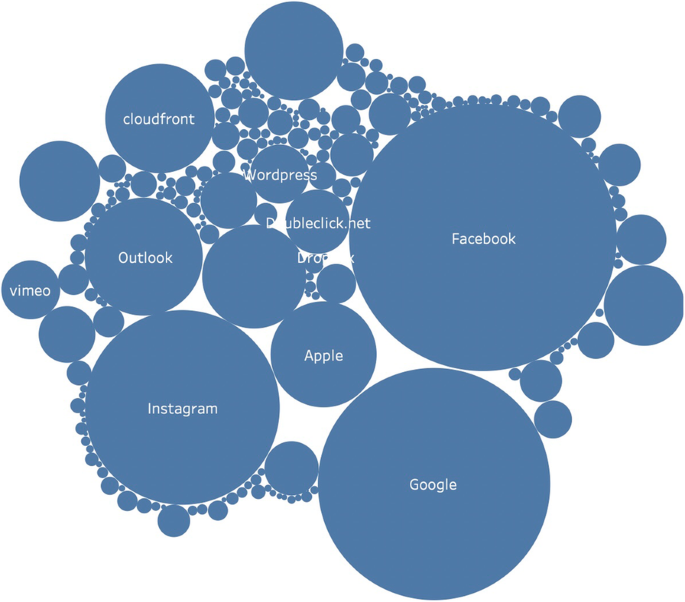

The preliminary findings suggest that the use of apps during the theoretical classes of the Department of Communication and Art is quite high and that the most used apps are Social networks like Facebook and Instagram. During this pilot the accesses during theoretical classes corresponded to approximately 11,177 accesses per student. We also concluded that the students agree that accessing applications can distract them during these classes and that they have a misperception about their use of online applications during classes, as the usage time is, in fact, more intensive than what participants reported.

The use of mobile devices by higher education students has grown in the last years (GMI, 2019). Technological advancements are also pushing society with consequent rapidly changing environments. Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are not exempted from these technological changes and advancements, and it is compulsory that they follow this technological evolution so that the teaching-learning process is improved and enriched.

HEI’s are trying to integrate digital devices such as mobile phones and tablets, and informal learning situations, assuming that the use of these technologies may result in a different learning approach and increase students’ motivation and proficiency (Aagaard, 2015).

In a study by Magda, & Aslanian (2018), students report that they access course documents and communicate with the faculty via their mobile devices, such as smartphones. Over 40% say they perform searches for reports and access institutions E-Learning systems via mobile devices (Magda, & Aslanian, 2018). The EDUCAUSE Horizon Report - 2019 Higher Education Edition (Alexander et al., 2019) also mentions M-Learning as the main development in the use of technology in higher education. However, teachers believe students use their gadgets less than they actually do, and mobile devices also challenge teaching practices. Students use devices for off-task (Jesse, 2015) or parallel activities and there may be inaccurate references to their actual use of mobile devices.

Mobile device users have very different usage habits of their devices and their applications, and it is important to study and characterize these behaviours in different contexts, as explained below. The reports that usually support these studies are made with questions directed to the users themselves asking them questions about the apps they have on the devices and the reasons for using them. However, Gerpott & Thomas (2014) argue that other types of studies are needed to properly support this type of research.

Studies are usually conducted in organizations, based on the opinion of the participants, and cannot be replicated and generalized, for example, regarding the use of the internet or mobile applications by the general public, because these devices, unlike desktop devices, can be used anywhere and at any time (Gerpott & Thomas,2014).

Furthermore, in mobile contexts, it becomes difficult for people to remember what they have used, because mobile applications can be used for various tasks, in various contexts, whether professional or personal, and the variety of applications, the use made, the periods of use are usually so wide and differentiated, that it can become difficult for users to refer which services or applications they have used, under which circumstances and how often. (Boase & Ling, 2013).

Thus, it is relevant, for several areas and especially for this research area, to have studies that cross-reference reported usage with actual usage. One of the ways to achieve this is with the use of logs of the use of mobile devices and applications, as mentioned by De Reuver & Bouwman (2015):

Using this approach this pilot study aims to create and validate a methodology:

i) to show the profile of these users,

ii) to reveal the kind of applications they use in the classroom and when they are in the institutions,

iii) and also, to compare the users’ perceptions with the real use of mobile applications.

Knowing the real usage and the usage students mention may provide valuable insights to teachers and HEIs and use this data for decision making about institutional applications to support students and teachers in their teaching and learning activities. Such information can also bring insights on the integration of M-Learning strategies, promoting interaction, communication, access to courses and the completion of assignments using students’ devices.

The central focus of this study is, therefore, to show preliminary results of the use of applications by students in class time during theoretical classes, through logs collected during class time.

The paper is divided into five parts. In the first part, relevant theoretical considerations are addressed, having in mind the current state of the art in terms of the literature and empirical work in this field. The second part outlines the study methodology. In the third part, the technological setting is highlighted. The cases and the results of the data analysis are described in the fourth part. Lastly, the results are interpreted, connected and crossed with the preliminary considerations.

The massive use of mobile devices has created new forms of social interaction, significantly reducing the spatial difficulties that could exist, and today people can be reached and connected anytime and anywhere (Monteiro et al., 2017). This also applies to the school environment, where students bring small devices (smartphones, tablets and e-book readers) with them, which, thanks to easy access to an Internet connection, keep them permanently connected, even during classes.

In HEIs there is also a growing tendency among members of the academic community to use mobile devices in their daily activities (Oliveira et al., 2017), and students expect these devices to be an integral part of their academic tasks, too (Dobbin et al., 2011). A great number of users take advantage of mobile devices to search information and, since they do not always have computers available, these devices allow them an easy access to academic and institutional information (Vicente, 2013).

One of the challenges educational institutions face today has to do with the ubiquitous character of these devices and with finding ways in which they can be useful for learning, thus approaching a new educational paradigm: Mobile Learning (M-Learning) (Ryu & Parsons, 2008).

M-learning allows learning to take place in multiple places, in several ways and when the learner wants to learn. As learning does not necessarily have to occur within school buildings and schedules, M-Learning reduces the limitations of learning confined to the classroom (Sharples, M., Corlett, D. & Westmancott, 2002), leading UNESCO to consider that M-Learning, in fact, increases the reach of education and may promote equality in education (UNESCO, 2013). The EDUCAUSE Horizon Report - 2019 Higher Education Edition (Alexander et al., 2019) also mentions M-Learning as the main development in the use of technology in higher education and, therefore, it becomes increasingly relevant to rethink learning spaces in a more open perspective, both physically and methodologically, namely through mobile learning that places the student at the centre of the learning process.

Quite often studies that intend to determine the use of mobile applications focus on general questions, but the most common ones are related to the frequency and duration of the use of these devices, for example, questions such as “how many SMS or calls are made?” or “how often do you use the device?”

In fact, instruments like questionnaires are widely used in this type of studies. However, since mobile devices are completely integrated in our daily life and we use them quite extensively, it is difficult to retain and define with plausible accuracy the actual use that we make of them.

It is therefore relevant to effectively understand how these students use these devices, more specifically the applications installed on them. To this end, most studies have been based on designs that are focused on the users’ perceptions and based are on these reports.

Thus, it was important to understand if what users report using corresponds to what they actually use, and if this use does not occur for distraction or entertainment, for example.

Considering the above, some studies have focused on the validity of the use of these instruments. One of these first studies, carried out by Parslow et al. (2003), aimed at determining the number of calls made and received in the days, weeks or months preceding the date of the questionnaire, and their duration. The answers were compared with the logs of the operators and it was concluded that self-report questionnaires do not always represent the actual pattern of use.

Finally, in self-report instruments, which refer to questions of daily activity on mobile devices, this activity may not represent a general pattern of activity, since from individual to individual the patterns of daily use may vary considerably and thus reflect a very irregular use.

In a study by Boase & Ling (2013), the authors mentioned that about 40% of studies on mobile device use, based on articles published in journals (41 articles between 2003 and 2010), are based on questionnaires.

The questions asked aim to estimate how long or what type of use they have made of their devices on a daily basis, and sometimes aim to know about time periods of several days. In most of these studies, 40% of papers use at least one measure of frequency of use and 27% a measure of duration of use that users make. Another factor that is mentioned is that users do not always report their usage completely accurately. On the other hand, the same study mentions that users may over or under report the use they make for reasons of sociability (Boase & Ling, 2013).

Given the moderate correlation between self-report instruments and data from records or logs (Boase & Ling, 2013), the author considers that researchers can significantly improve the results if they use, together with other instruments, data from logs to make their studies more accurate and rigorous. Another suggestion would be the use of mobile applications that record these usage behaviours (Raento et al., 2009).

Indeed, this kind of instrument is widely used in this type of studies. However, given that mobile devices are fully integrated into our daily lives and we use them quite extensively, it becomes difficult to retain and define with plausible accuracy the use we make of them. In addition to the factors mentioned in the previous paragraph, it is important that these types of studies are validated with other methods, such as the use of logs, as presented in this study. The logs in this study refer to the capture records of the mobile device traffic made by the students.

This article therefore aims to present preliminary results with an approach that uses cross-checking of log data with questionnaire results.

This article intends to present and discuss preliminary results of a study that aims to characterize the use of mobile applications at the University of Aveiro through collected logs, crossing its results with questionnaires answered by students during the classes, and also with an observation grid with data from the analysed class and questions to teachers related to what teachers recommend regarding the use of mobile phones during class time.

The research question that motivated this article is: which digital applications/services are most frequently used on mobile devices by the students of the University of Aveiro during their classes?

The study was composed of 40 students, that answered the questionnaires.

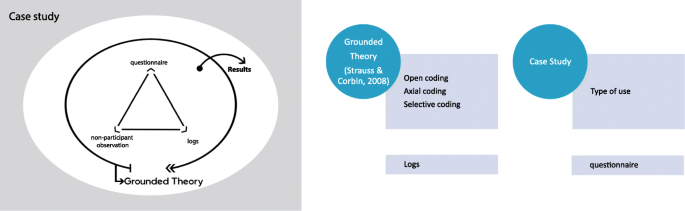

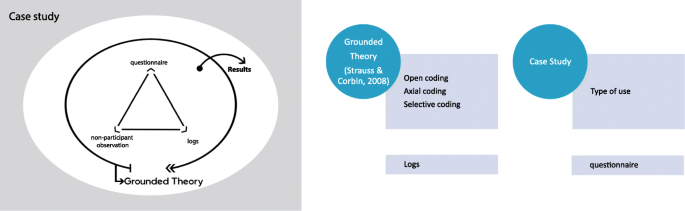

The research was based on the Grounded Theory method aiming to analyse the logs from the access points of the University. With the collected data, a usage profile of mobile devices during classes was drawn.

Figure 1 presents a diagrammatic representation of the created methodological process.

Therefore 3 instruments were used for the data collection: a questionnaire, an observation grid and logs collected through mobile traffic in the wi-fi network of the university.

The questionnaire allowed for a quantitative assessment of the profile of the participants and collected data on the use that participants claimed to make of their mobile devices. The observation grid served as a guide for the implementation of the study, allowing to record data on the classes where the collections took place and to verify whether certain items were present, such as permission to use mobile devices or planning to use them by teachers. The observation grid would also serve to make the link between use and content in class, but in this pilot, it was not possible to make this link between the class content and the usage of mobile applications, because the author could not observe the applications used by students.

The database containing the usage records enabled the analysis of the logs, resulting in the quantification and verification of the type of activity that each (anonymous) participant made of their device.

The 3 instruments used aimed to i) determine which application(s) students were really using during the classes, through the analysis of the data logs collected from the Wi-Fi network of the University; ii) identify the participants’ representations of their activities by means of several questions regarding mobile usage during class time; iii) observe students’ behaviour and focus via an observation grid that was used by the researcher/observer when he was attending the classes.

The group who participated in this pilot study was selected in accordance with the professors and classes available, so it is considered a convenience sample. The group was constituted by students of undergraduate classes from the Communication and Arts Department of the University of Aveiro.

Table 1 summarizes the schedule of the pilots carried out, the curricular units where they took place, their duration and the instruments used. For ease of management, all the pilots took place in the same department of the University.

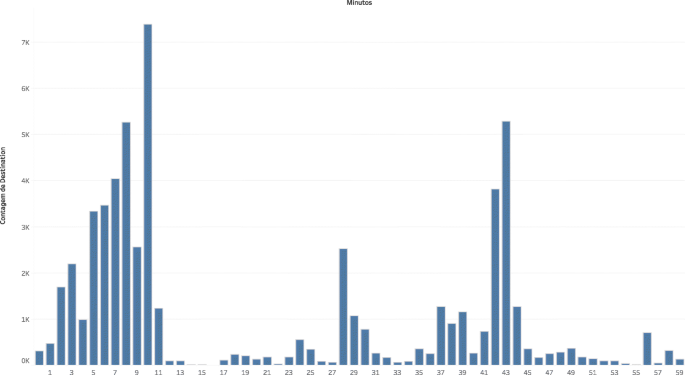

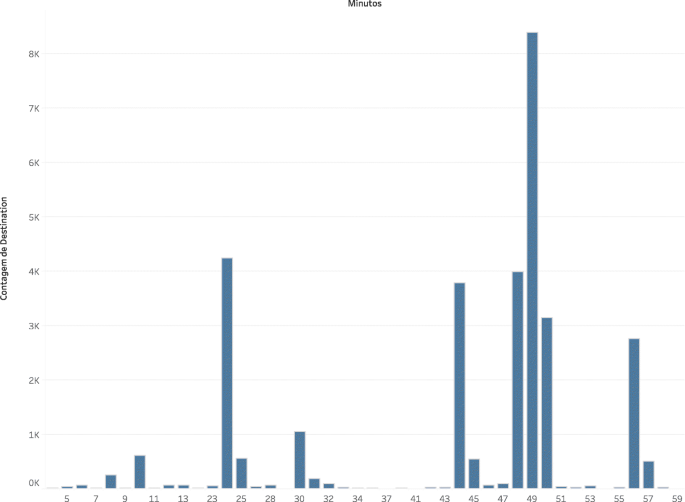

Another noticeable preliminary result is that students use Facebook more at the beginning of classes and Instagram is used more at the end, as we can see in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5.

In addition, the developed model was used in the main study with a bigger convenience sampling approach, which may provide a more accurate representation of the population of mobile-phone-users in the study field.

The visualizations created in a dynamic way during this study showed that the use of logs as a complementary data provider to other instruments, such as questionnaires, can be an added value for this research field.

On the other hand, this pilot contradicts (sometimes slightly, others considerably) the results of the questionnaires answered by the students and whose logs were collected and analysed. Logs show that:

The students’ perception of the “use of mobile devices and applications during lessons”, and as already mentioned, during a teaching activity - 70% of the students refer using the applications between 1 to 5 times, 22% between 6 to 10 times and 4% more than 10 times. It should also be noted, as previously mentioned, that only 4% mention not using them. With regards to the use during the week, 56% of the students refer using them between 4 to 5 days per week and 39% between 1 to 3 days per week. There is also a relatively low percentage of students mentioning that they use the devices during class more than ten times (4%).

However, analysis of the logs shows that this use appears to be much more intensive. We performed a calculation based on the average number of accesses, from which we removed 40% of potential automatic accesses and divided by the average number of accesses each application had in the initial test. The results present 6.6 accesses to the device per class/student in the class with the fewest accesses, and for the highest case, 313 accesses to the device per class/student.

This result is reinforced by results from other studies, such as the Mobile Survey Report, which states that students make regular use of laptops and smartphones during lessons (Seilhamer et al., 2018).

These conclusions lead us to some very serious insights on this subject. Apparently, even older students have a misperception of their use of online applications during classes. There is a serious discrepancy and incongruency between the behaviours that they claim to adopt and those they actually engage in during the classes. There are authors, who argue for the need for other types of studies that support this type of approach (Gerpott & Thomas, 2014), because the perception reported by users may not correspond to the actual use. It means that this gap deserves a deeper reflection. Why does it happen? Are students not motivated in higher education? Is the world offered online more interesting than the one in the physical campus? We will try to answer these questions in the main study.

Some of the visualizations created are publicly available at https://public.tableau.com/profile/davidoliveiraua

HTTPS It is a protocol used for secure communication over a computer network, and is widely used on the Internet

IP is the s a numerical label assigned to each device connected to a computer network that uses the Internet Protocol for communication

PHP is a general-purpose scripting language especially suited to web development DNS is naming system for computers, services, or other resources connected to the Internet Unformatted file where values are separated by commasHigher Education Institutions

Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure

Domain Name System