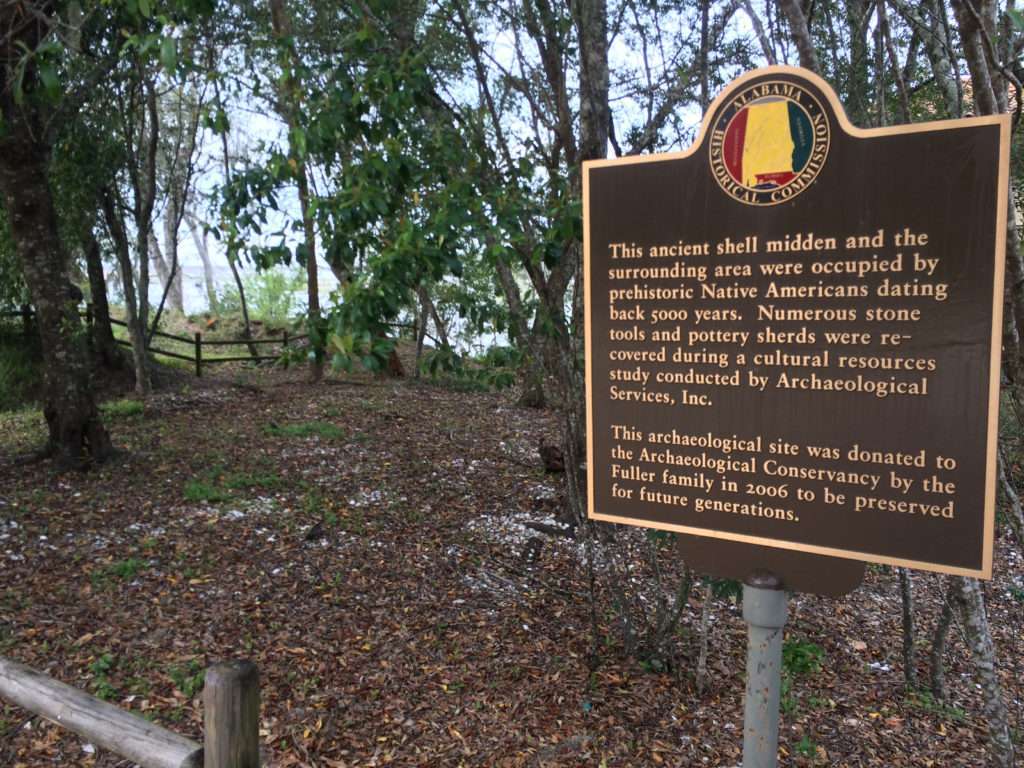

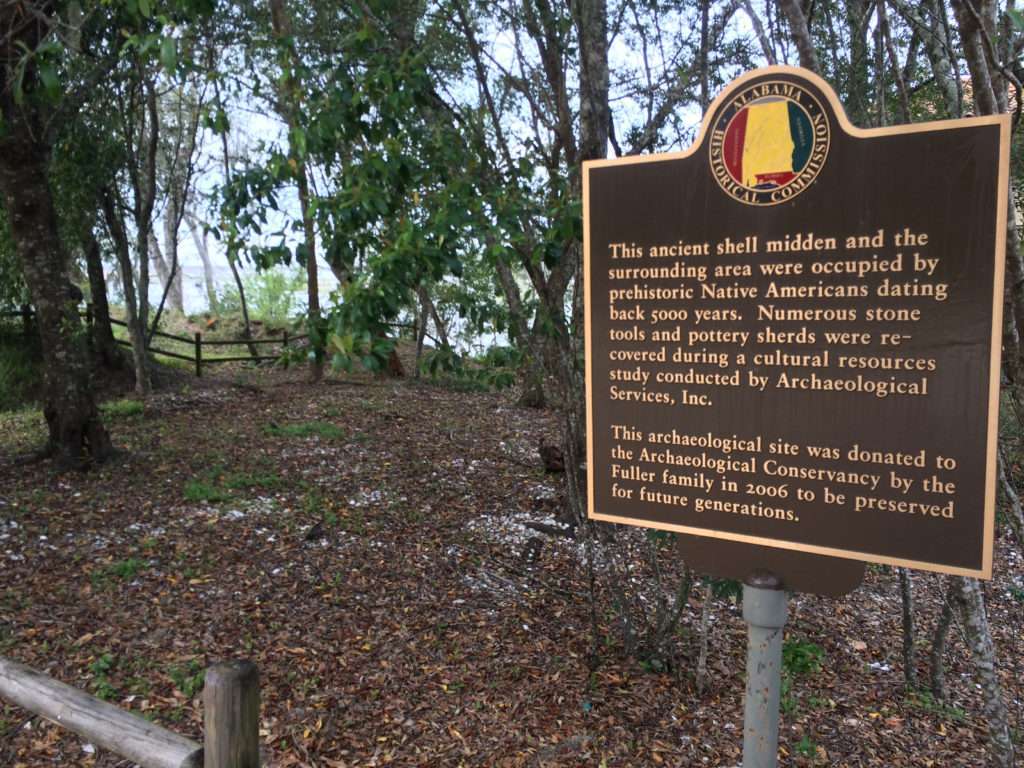

Since at least 3,000 BC, the Mobile Tensaw Delta and Mobile Bay teemed with indigenous people moving up and down the waterways and taking overland trails to places far inland where they traded items and ideas. Atop this bluff overlooking both the delta and the bay, in what has become the community of Spanish Fort, lie the remains of repeated occupation left behind by these people.

The Fuller site consists of a shell midden formed by the remnants of countless gatherings and meals. Rangia shells piled across the site highlight the importance of the brackish water clams that helped to feed all the people living and working in the area.

Beginning in the Middle Archaic period, some 5,000 years ago, mobile groups of people who hunted and gathered their food took advantage of this strategic location and occupied it regularly. In addition to being close to abundance sources of food, fresh water, and other essential resources in the delta and bay, this site’s relatively high elevation protected it from floods and storm surges. Nearby outcrops of iron-rich sandstone also offered material suitable for making stone tools, which is rare along the Golf Coast. About AD 150, the site was occupied again during the Middle Woodland period and yet again during the Mississippian Stage after about AD 1100, attesting to this site’s attractiveness as a place for indigenous people to camp and live over the millennia.

The strategic value of this site was evident hundreds of years later, when in the Spring of 1865, Union African American troops built a series of artillery batteries in this area to take advantage of the strategic firing position that the high bluff afforded. One of those earthworks disturbed the shell midden significantly, and the remnants of these fortifications are still visible.

This site is very important to numerous Southeastern indigenous tribes who assert an ancestral connection with those who built and occupied Alabama’s ancient mounds. The earthwork landscapes and the objects and information recovered from them reveal a rich cultural tradition that still thrives today among these tribes. Our indigenous mound sites represent a heritage for all Alabamians to cherish, and it is important that we protect and preserve them for future generations.

The cluster of mounds known as the Bessemer Site was the largest indigenous mound site in what is now Jefferson County, and it once dominated a large territory in what became north-central Alabama. Occupied from about AD 1150 to 1250 during the early Mississippian period, the site included three mounds near the confluence of Halls Mill Creek and Valley Creek west of Downtown Bessemer. In the 1930s, archaeologists completely excavated all three mounds, so no above-ground evidence of them remains. These mounds included a “domiciliary” (residential) mound, a small burial mound, and a large ceremonial mound. The two-tiered ceremonial mound was built atop an unusual stone foundation that is rarely seen associated with mounds in the Southeast. Other unique features included preserved stair-steps on the domiciliary mound and the remnants of a double-walled palisade encircling the burial mound. Beneath the mounds, archaeologists also discovered the remains of buildings and other structures that pre-dated construction of the mounds.

During the mounds’ occupation, an active village surrounded the site where people lived in rectangular wattle and daub houses with thatched roofs. In the bottomlands along Valley Creek beyond the mound center, members of this community cultivated important food crops such as corn, beans, squash, amaranth, and sunflower, and supplemented these crops by gathering fruits and nuts, hunting game, and fishing.

The Bessemer Site has played an important and changing role in the interpretation of Mississippian cultural developments in central Alabama. Early studies of pottery from the site suggested a close association with the Moundville Chiefdom, which is located 75 miles downstream along the Black Warrior River. However, a more recent and better understanding of Mississippian ceramics indicates that the Bessemer Site was actually the center of a separate chiefdom that was similar to Moundville, but distinct from it.

This site is very important to numerous Southeastern indigenous tribes who assert an ancestral connection with those who built and occupied Alabama’s ancient mounds. The earthwork landscapes and the objects and information recovered from them reveal a rich cultural tradition that still thrives today among these tribes. Our indigenous mound sites represent a heritage for all Alabamians to cherish, and it is important that we protect and preserve them for future generations.

Centered around Boiling Spring, the Choccolocco Creek Archaeological Complex once consisted of at least three earthen mounds, a large stone mound and a large snake effigy (representation), also made of stone. The largest earthen mound once stood high above the Choccolocco Creek floodplain. The earliest earthen mound construction at the site began during the Middle Woodland period (ca. 100 BC to AD 250) when the site became a regionally important ritual center connected through cultural exchanges with groups living on the Gulf Coastal Plain to the south and the Tennessee Valley to the north. Mound construction appears to have resumed at the site around AD 1100 when the inhabitants of the Choccolocco Valley were closely connected with the people of the Etowah site near present-day Cartersville, Georgia.

Prior to the 1830s, the Choccolocco Creek Archaeological Complex was the location of the ceremonial ground of the Abihkas, one of the most ancient tribal towns within the modern Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Ethnographic research conducted by the Smithsonian Institution in the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries indicates that the stone constructions associated with the complex are associated with oral histories that tell of a town “lost in the water.” The large stone mound is thought to be the result of “burden” stones carried by the Abihka in remembrance of those lost in a great flood.

This site is very important to numerous Southeastern indigenous tribes who assert an ancestral connection with those who built and occupied Alabama’s ancient mounds. The earthwork landscapes and the objects and information recovered from them reveal a rich cultural tradition that still thrives today among these tribes. Our indigenous mound sites represent a heritage for all Alabamians to cherish, and it is important that we protect and preserve them for future generations.

Gulf State Park holds some of the most endangered archaeological deposits in the State of Alabama. Even though these sites are located within the protected area of the park, rising sea levels and damage caused by severe coastal storms will one day likely erase what remains of these fragile reminders of the people who were here before us. Even today, understanding the complex system of interconnected waterways, residential sites, and mounds is made that much more difficult by the centuries of storms and historic changes to the landscape.

The park has both sand and shell mounds that were built during the Middle Woodland period (circa AD 150) and Mississippian Stage (AD 1000 to 1500). Sand mounds are common along the Gulf Coast and served as both cultural markers for the living and memorials to the dead. The shell mounds located at the park are typically elongated midden (refuse pile) deposits bordering the water’s edge or circular mounds with intentional design. While some mounds include a mix of different shellfish types, a few show preference for only one type of shell, such as the Rangia cuneata, a brackish water clam common in the marshes of the Gulf Coast. The selection of this single type is unusual given the availability of other shellfish that exist in the same areas and suggests that those who built the mounds were selecting them for a special reason. They may have been selecting them based on ease of harvest, season of availability, cultural taboos against eating other types, or maybe something as simple as taste.

When we think of these people who hunt and gather their food, we often think of a simple lifestyle that included hunting, fishing, collecting seasonally available fruits and nuts, and limited agriculture. In reality, these people were engineering large communal buildings, digging canals, building mounds, trading over long distances, and practicing complex cultural activities that included intricate artwork and a highly structured social hierarchy with religious, political, and social leaders, warriors, and venerated elders. Imagine trying to convince one hundred of your friends to go build a mound, one basket load of sand at a time for days on end, or dig a long canal that would allow your town to have direct access to protected bays and inlets without having to venture out into the rough open waters of the Gulf. The people who built these things lived in a complex world of interacting cultures, languages, and beliefs much like we do today.

Gulf State Park is one of the few places where remnants of these past lifeways are preserved.

This site is very important to numerous Southeastern indigenous tribes who assert an ancestral connection with those who built and occupied Alabama’s ancient mounds. The earthwork landscapes and the objects and information recovered from them reveal a rich cultural tradition that still thrives today among these tribes. Our indigenous mound sites represent a heritage for all Alabamians to cherish, and it is important that we protect and preserve them for future generations.

During the Late Woodland period around AD 700-1100, people living at the confluence of the Chatuga, Coosa, and Little Rivers established one of the largest and most elaborate communities in the region. At the time, populations were on the move and groups from the Tennessee River and Black Warrior River Valleys to the north and west were beginning to settle in an area that had traditionally been occupied by people associated with cultures centered in northwest Georgia. The appearance of these new groups may not have always been peaceful as protective palisades were built around several of the villages. In addition, some villages were intentionally built on high ground with clear views of the river bottoms.

These new people built villages along the banks of the Chatuga, Coosa, and Little Rivers. The Coker Ford site overlooks the Little River and includes the largest of these villages along with two unusual stone-covered earthen mounds built to memorialize their ancestors.

By studying the pottery styles made and used at these sites, archaeologists believe that their culture originated in the Tennessee River Valley near Guntersville and that they had moved to the area in search of new opportunities. They brought new ideas and technologies with them, but quickly began to take on some of the cultural traits of the people who already occupied the area. In fact, their influence may have been directly linked to the development of the large Mississippian mound complex of Etowah, near the head of the Coosa River in northwest Georgia. Etowah grew to control a vast area of the Upper Coosa River Valley and was likely one of the larger towns the Spanish encountered during their first exploration of the Southeast in 1541. By then, the Coker Ford site had long been abandoned and the mounds left as a monument to the ancestors.

This site is very important to numerous Southeastern indigenous tribes who assert an ancestral connection with those who built and occupied Alabama’s ancient mounds. The earthwork landscapes and the objects and information recovered from them reveal a rich cultural tradition that still thrives today among these tribes. Our indigenous mound sites represent a heritage for all Alabamians to cherish, and it is important that we protect and preserve them for future generations.

Due to the remote and inaccessible location of the site, the map indicates the location of the interpretive sign.